Today is the Winter Solstice – the shortest day of the year, and the first day of winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

The 200-year-old formula used by the Old Farmers’ Almanac predicts that “this winter is expected to be a bit more 'normal' as far as the temperatures are concerned, especially in the eastern and central parts of the country–chiefly those areas to the east of the Rocky Mountains–with many locations experiencing above-normal precipitation.”

Since we’re in the bug business, we often get asked what insects do in winter. Does a harsh winter and heavy snowfall result in fewer bugs?

The answer, typically, is no. Insects have several ways to deal with cold weather. Some simply migrate. Some are freeze-tolerant thanks to compounds in their bodies called “cryoprotectants”, which is similar to antifreeze. Heavy snowfall on the ground acting as an insulation layer might even help many insects survive the harsh winter,

Many insects overwinter by entering a state of either diapause or hibernation. During this period, their metabolism slows and they run off stored food/energy reserves in their bodies until temperatures rise and they become active again.

Most of the insects we deal with go into hibernation, not diapause. What’s the difference? Simply put, diapause is a physiological dormancy in any stage of an insect’s development induced by certain adverse environmental conditions, while hibernation is inactive winter sleep.

Temperature isn’t the only factor that triggers the insects to overwinter. Shorter days in the lead-up to winter signal to the insects’ bodies that it’s time to hibernate.

The overwintering site – and the length of that overwintering – is important. If insects emerge from diapause or hibernation too early, they will be exposed to harsh conditions – Stable temperatures are best, as opposed to a frequent freeze-thaw cycle. The latter can cause insects to emerge too early, thinking it’s spring. They can succumb to harsh conditions once the weather goes from thaw back to freeze.

Here’s how some insects react to winter weather:

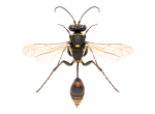

Yellowjackets, wasps and hornets: Only the newly fertilized queens survive at the end of the season. These queens will spend the winter months hibernating in sheltered locations like tree stumps, under debris, or inside attics or wall voids. They emerge during the first warm days of spring to look for new nest sites.

Stink bugs: Adults enter homes in fall for a warm place to spend the winter. Once indoors, they go dormant and live off stored energy reserves from their fall consumption of fruit, vegetables and foliage. When their food stores run out, or the sun comes through the winter and warms their hiding spot, or the area experiences an unseasonably warm period (think Pittsburgh’s mid-60 degree temperatures in February 2011) they think it’s spring and start moving around inside the home looking for a way outside.

Asian ladybugs: Adults enter homes through small cracks around windows and doorways and gather in groups to hibernate.

Flies: Most common spend the winter in either the larval or pupal stage under manure piles, organic matter or in other protected locations.

Cluster flies. Adult flies enter houses in large numbers and spend the winter in “clusters” in walls, attics and basements of a home, and also often in the corners of a room or near windows.

Mosquitoes: The males die at the end of the season, and only the females overwinter, hibernating in hollow logs. Some species spend winter in the larvae or pupa stage and suspend their development until the weather warms.

Japanese Beetles: After the summer mating season, the grubs burrow deep into the soil in August/September and hibernate until spring when the weather warms up. They then wake from their winter nap, move toward the surface, and begin feeding on the roots of turf grasses.

Pantry and Birdseed Moths: Adult moths become lethargic and the development of eggs, larvae and pupae slows down.

Ants: They eat large amounts of food in the fall to prepare for winter hibernation. As the temperatures drop, they become sluggish and then spend the cold months in warm places (under soil, tree bark or rocks… or indoors), resuming activity in the spring.

Ants: They eat large amounts of food in the fall to prepare for winter hibernation. As the temperatures drop, they become sluggish and then spend the cold months in warm places (under soil, tree bark or rocks… or indoors), resuming activity in the spring.

The bigger determining factor in an insect problem is the onset of spring temperatures. Generally speaking, the earlier the spring weather, the faster insects get established.

So as most insects settle down for a long winter’s nap, you can enjoy your snowy wonderland free of bugs… for now.

Ant Baits

Ant Baits Birdseed Moth Trap

Birdseed Moth Trap Fly Trap Max

Fly Trap Max Fly Trap, Big Bag

Fly Trap, Big Bag  Fly Trap, Disposable

Fly Trap, Disposable Fly Trap, Fruit Fly

Fly Trap, Fruit Fly Fly Trap, POP! Fly

Fly Trap, POP! Fly  Fly Trap, Reusable

Fly Trap, Reusable FlyPad

FlyPad Japanese & Oriental Beetle Trap

Japanese & Oriental Beetle Trap Spider Trap

Spider Trap TrapStik, Carpenter Bee

TrapStik, Carpenter Bee TrapStik, Deck & Patio Fly

TrapStik, Deck & Patio Fly  TrapStik, Indoor Fly

TrapStik, Indoor Fly TrapStik, Wasp

TrapStik, Wasp W·H·Y Trap for Wasps, Hornets & Yellowjackets

W·H·Y Trap for Wasps, Hornets & Yellowjackets Yellowjacket Trap, Disposable

Yellowjacket Trap, Disposable  Yellowjacket Trap, Reusable

Yellowjacket Trap, Reusable  Ants

Ants Biting Flies

Biting Flies Carpenter Bees

Carpenter Bees Flies

Flies Fruit Flies

Fruit Flies Hornets

Hornets Japanese Beetles

Japanese Beetles Mud Daubers

Mud Daubers Oriental Beetles

Oriental Beetles Birdseed & Pantry Moths

Birdseed & Pantry Moths Spiders

Spiders Wasps

Wasps Yellowjackets

Yellowjackets