(Continued from Part 2)

"That sales call was a disaster," Schneidmiller explains, “The buyer basically laughed us out of the place by saying, ‘Why would someone trap an insect when they can spray an insect?’”

Schneidmiller fired the rep and went back to selling the product himself from the back of his pickup truck throughout within Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho. “At that time we were selling in Coeur d’Alene, Spokane, Pullman – wherever I stopped, I would try to sell something. But we were spending more money than we were bringing in.

“One thing that first sales rep did right, however,” he adds, “was to put us in his booth at the Far West Show. I was in the corner behind the sleds and the shovels with our fly trap and our yellowjacket trap. Nothing came of it initially, aside from a few orders. Then one day I got a call from the Vice President of Marketing for Kelley Manufacturing in Houston, Texas.”

The executive had seen Schneidmiller’s products at the Far West show and tried them out himself, with great success.

Kelley Manufacturing wanted to diversify their lawn & garden offerings and leverage their tremendous distribution. They offered to fly Schneidmiller down to their headquarters for a meeting.

“At that time, no one was selling insect traps on a national scale,” he recalls. “They took me to their glass offices and said they were going to take us national. They said, ‘you'll do the developing and the manufacturing, and we’ll do all the marketing’. They didn’t mince words – they said they would be showing up to our offices with 40 foot trailers and maxing them out.”

Calculating in his head the number of traps a 40-foot trailer would hold, Schneidmiller’s eyes widened. At that time, he had only sold 100 cases to any one account.

Calculating in his head the number of traps a 40-foot trailer would hold, Schneidmiller’s eyes widened. At that time, he had only sold 100 cases to any one account.

“Not knowing all the other aspects of the business, I thought this sounded like a pretty slick, clean way to go,” he said. “So we signed a deal for the rest of the IPC stuff that year.”

This time, the promise was kept and the trucks appeared. Filling up these 40-foot trucks made Sterling’s sales numbers jump off the charts.

The plan after that was to rename the product “Kelley’s Killers”. “Part of the agreement with Kelley Manufacturing was that we would lose our label,” he explains.

At the same time, Schneidmiller was working on an idea based on feedback from customers who loved the fly trap, but complained about cleaning it out. “A woman was buying it and throwing it away each time,” he said. “That’s when I had the idea of making it a disposable trap. I glued a bag on the bottom of the lid, and it caught flies.”

Researching flexible packaging options, Schneidmiller came up with a design that would work for mass production. “I proposed it to Kelley Manufacturing and they were so enamored with it they gave us a purchase order for 400,000 of them. I just said, ‘WOW’. They told me that was just the beginning.”

Researching flexible packaging options, Schneidmiller came up with a design that would work for mass production. “I proposed it to Kelley Manufacturing and they were so enamored with it they gave us a purchase order for 400,000 of them. I just said, ‘WOW’. They told me that was just the beginning.”

Schneidmiller ramped up production for this order by purchasing an expensive custom mold and placing an order with a bag manufacturer. He worked with another vendor to make a water-soluble pouch to hold the attractant.

For the first time in Sterling’s existence, the company had to borrow some of the money on his line of credit to produce everything and be ready to go for the pending orders. It was a staggered purchase order, with the first shipments going out in October.

“Fifteen days before we were supposed to make our first shipment, I got a call in the afternoon from the president of Kelley Manufacturing,” said Schneidmiller. “He sounded disturbed; he was using obscenities and slurring his words. I listened to this drivel coming from him and couldn’t get a word in edgewise. Finally, he flat-out said, ‘We’re out of business, we’re not purchasing anything, good-bye.’”

Hundreds of thousands of “Kelley’s Killers” bags were sitting in the back of the building.

Ant Baits

Ant Baits Birdseed Moth Trap

Birdseed Moth Trap Fly Trap Max

Fly Trap Max Fly Trap, Big Bag

Fly Trap, Big Bag  Fly Trap, Disposable

Fly Trap, Disposable Fly Trap, Fruit Fly

Fly Trap, Fruit Fly Fly Trap, POP! Fly

Fly Trap, POP! Fly  Fly Trap, Reusable

Fly Trap, Reusable FlyPad

FlyPad Japanese & Oriental Beetle Trap

Japanese & Oriental Beetle Trap Spider Trap

Spider Trap TrapStik, Carpenter Bee

TrapStik, Carpenter Bee TrapStik, Deck & Patio Fly

TrapStik, Deck & Patio Fly  TrapStik, Indoor Fly

TrapStik, Indoor Fly TrapStik, Wasp

TrapStik, Wasp W·H·Y Trap for Wasps, Hornets & Yellowjackets

W·H·Y Trap for Wasps, Hornets & Yellowjackets Yellowjacket Trap, Disposable

Yellowjacket Trap, Disposable  Yellowjacket Trap, Reusable

Yellowjacket Trap, Reusable  Ants

Ants Biting Flies

Biting Flies Carpenter Bees

Carpenter Bees Flies

Flies Fruit Flies

Fruit Flies Hornets

Hornets Japanese Beetles

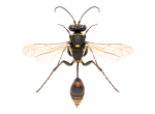

Japanese Beetles Mud Daubers

Mud Daubers Oriental Beetles

Oriental Beetles Birdseed & Pantry Moths

Birdseed & Pantry Moths Spiders

Spiders Wasps

Wasps Yellowjackets

Yellowjackets